Following the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, banking regulators appeared on Capitol Hill last week. Fed Vice Chair for Supervision Barr and FDIC Chair Gruenberg testified before the Senate Banking and House Financial Services Committees about the recent bank failures. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation estimates it will cost $22.5 billion to backstop both Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, guaranteeing all deposits.

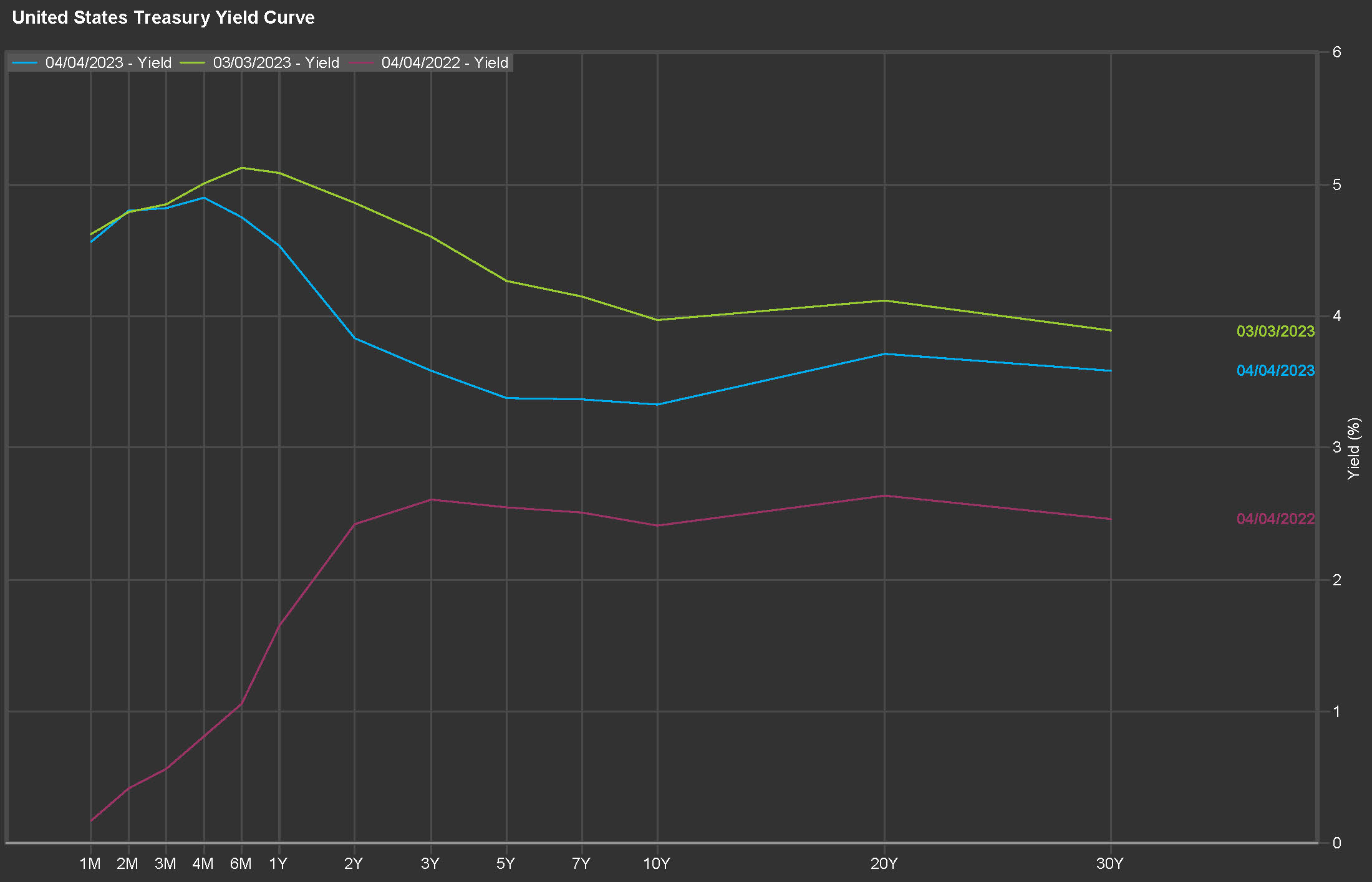

After the initial shock of these bank failures and the heightened sensitivity around bank holdings, the market rapidly adjusted to the new risks with the quickest monetary tightening in 44 years. Still, banks face several headwinds. First, the yield curve remains inverted—longer-term interest rates are lower than short-term rates. For example, the 10-year Treasury is yielding 3.38%, while the Fed Funds rate is 5%. This inversion is the largest in 42 years. It is generally viewed as a bearish signal for the economy, where the bond market is predicting the Federal Reserve will have to cut interest rates to stimulate a weak economy. As a result of the current yield curve, banks will need to pay depositors a competitive rate closer to 5% while they only receive interest of 4% or less on their longer-term loans.

Second, there is concern around banks’ susceptibility to the downturn in commercial properties. Prior to the pandemic, banks lent billions based on the collateralized values of office buildings. Post-pandemic, the work environment has changed and now a significant number of employees work from home. Thus, businesses no longer need as much office space and are letting leases expire or leasing smaller spaces. As a result, the values of office buildings have plummeted, especially in big cities like San Francisco, Los Angeles, Portland, and Seattle. For example, The Wall Street Journal recently reported that Blackrock relinquished a $650MM building in Los Angeles back to the lending bank. That bank must now hold this asset until the office property market improves (which could be years) or sell into a stressed market for presumably far less than the loan amount. Many commercial loans are upside down (loan amount larger than the property value) and owners will be increasingly relinquishing properties back to lenders. This creates a problem for the banks not only because values have fallen significantly, but there really isn’t a market to sell these properties right now and banks would face significant losses if forced to sell. Additionally, these properties do not qualify for short-term liquidity loans from the Fed’s new Bank Stabilization Program, which allows banks to get short-term loans at the par value of certain assets.

Third, there is apprehension around credit contraction. Faced with concerns about their own liquidity and their level of uninsured deposits, banks will undoubtedly be more selective when lending and less willing to tie-up precious cash in longer-term loans. The end result is banks limiting loans to the most creditworthy borrowers, which translates into a general credit contraction in the U.S. economy.

If there is a downturn in the economy, or even a recession, banks will need to increase reserves for loan losses as well. This can become negatively circular—banks’ own credit contraction leads to a downturn in the economy which, in turn, leads to a greater default rate on banks’ underlying loans.

Inflation might be yesterday’s problem.

Disclosures

This material is solely for informational purposes and shall not constitute a recommendation or offer to sell or a solicitation to buy securities. The opinions expressed herein represent the current, good faith views of the author at the time of publication and are provided for limited purposes, are not definitive investment advice, and should not be relied on as such. The information presented herein has been developed internally and/or obtained from sources believed to be reliable; however, neither the author nor Manchester Capital Management guarantee the accuracy, adequacy or completeness of such information.

Predictions, opinions, and other information contained in this article are subject to change continually and without notice of any kind and may no longer be true after any date indicated. Any forward-looking predictions or statements speak only as of the date they are made, and the author and Manchester Capital assume no duty to and do not undertake to update forward-looking predictions or statements. Forward-looking predictions or statements are subject to numerous assumptions, risks and uncertainties, which change over time. Actual results could differ materially from those anticipated in forward- looking predictions or statements. As with any investment, there is the risk of loss.

A consistent request from almost all families Manchester has served over the last thirty years is for guidance on how to talk about money. Both...

Manchester Capital's Managing Director, Christine Kaming Tomas recently sat down with Rabbi Yechezkel "Zeke" Moskowitz, a third-generation business...

Investing is more than a financial exercise. The most seasoned investor feels a twinge of fear and concern when volatile markets react negatively to...