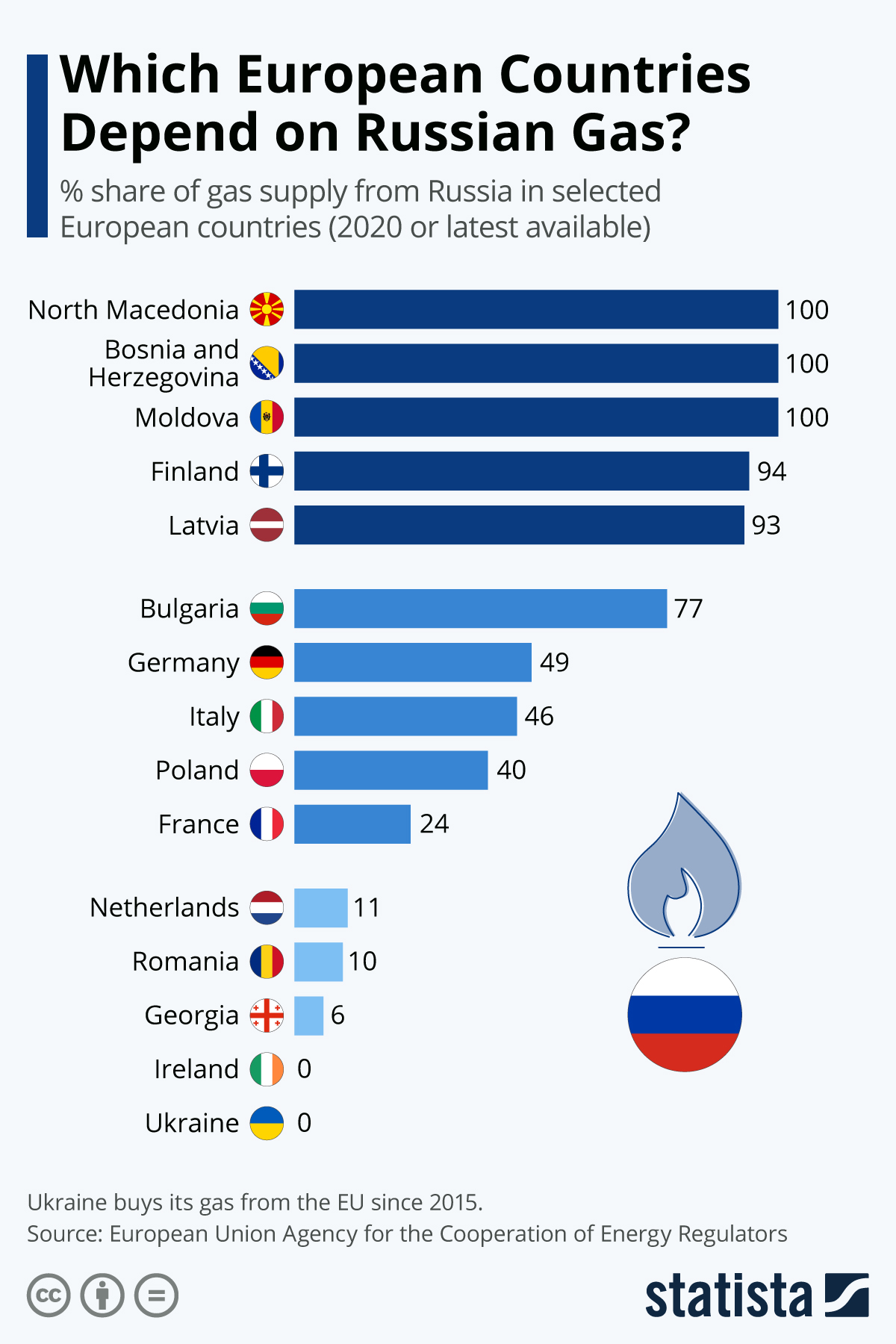

Ever since Russia attacked Ukraine on February 24th, the United States and Europe have placed a renewed focus on energy security. As the West imposes sanctions on Russia—the world’s number three oil producer and number two natural gas producer—many countries are trying to cope with a sudden decrease in energy supply that has caused energy prices to spike dramatically. Unfortunately, there are no easy answers.

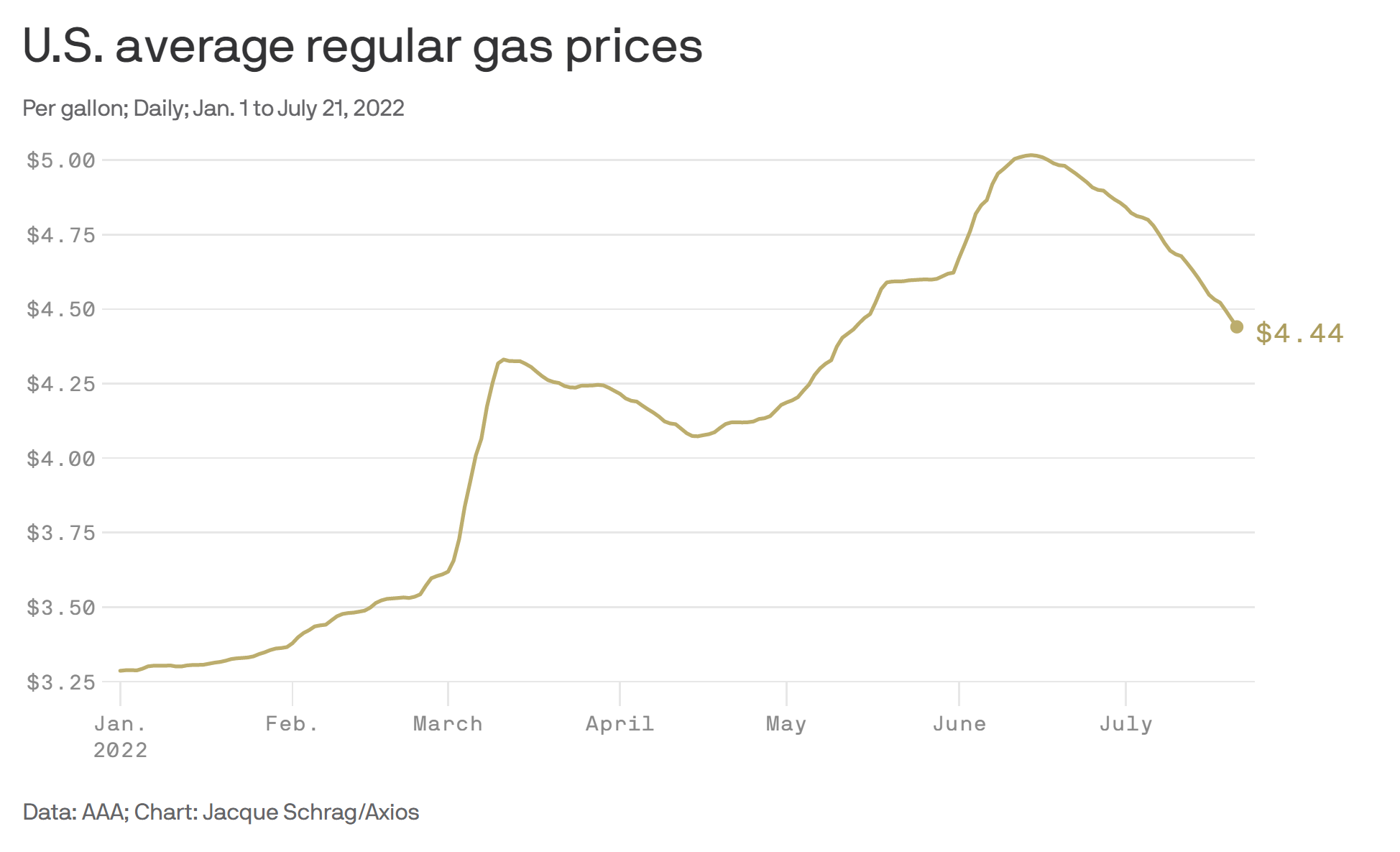

The decrease in supply caused by the sanctions against Russia is being felt far and wide—in the U.S. in the form of $5/gallon gasoline[1]; in the U.K. where average annual consumer energy costs will reach £3,250 per household in October, up from £1,277 before the invasion[2]; in Germany where electricity prices have risen 68%[3]; and in the Netherlands where electricity prices are up 200% from a year ago[4].

Solutions are being sought on both the demand side and the supply side. The European Commission has asked European Union member states to cut their natural gas use by 15% over the coming months[5]. A recent survey of 3,500 industrial companies in Germany found that 16% are scaling back production due to soaring energy prices[6]. Governments in many Western European countries are telling their citizens to brace for a complete shutoff of Russian energy supplies—this winter could be difficult. In the U.S., high gasoline prices (and high inflation) are causing consumers to drive less, reducing demand and causing gas prices to retreat some. Economic issues in China, the world’s second largest crude oil consumer, has also led to a slight reduction in global demand.

On the supply side, the U.S. is releasing approximately one million barrels of oil per day from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve[7]. President Biden recently traveled to Saudi Arabia to ask the Saudis to boost oil output, something that the Saudis, as members of OPEC, cannot unilaterally do. OPEC did pledge to increase oil production in July and August by 648,000 barrels/day[8] but is so far lagging that target. Beyond this pledge, OPEC and its allies, known as OPEC+, are unlikely to increase output substantially because doing so would threaten their alliance with Russia. There are other countries with spare capacity such as Libya (which has political issues), Iran (under sanctions), and Venezuela (also under sanctions), but the politics make utilizing each of them difficult. Though the Biden Administration asserted that they would ramp up domestic production—the U.S. was producing 12.3MM barrels/day in 2019 and now is only producing 11.6MM barrels/day as of May 2022[9] – it is no guarantee that it will reach pre-COVID 19 levels, let alone produce additional output, as the Administration is simultaneously committed to eliminating fossil fuels. Even if the U.S. could increase production, there is a limit to refining capacity. Six oil refineries that refined more than one million barrels a day have shut down since 2020. Coming into 2021 off the pandemic, the U.S. experienced the lowest annual refining capacity in six years. And the U.S. is not building any new refineries- the last one was in 2019- and before that the newest was built in 1977. [10]

U.S. Crude Oil Production – Historical Chart

Data and chart are from https://www.macrotrends.net/2562/us-crude-oil-production-historical-chart

Looking at immediate supply and demand are not the only possible solutions. Some U.S. states have floated the idea of sending checks to consumers to offset high energy costs (California comes to mind). Unfortunately, that approach doesn’t address either the supply or demand aspect and would be inflationary, driving gas prices higher by artificially subsidizing demand. The most obvious solution, a resolution to the Russia/Ukraine war, might solve the supply issue in the short term, or it might not. Western countries might still impose sanctions on Russia and will ultimately still want to shift to other energy sources.

That shift is already underway. As Russia has reduced the amount of natural gas it sends to Germany through the Nord Stream 1 pipeline to 20% capacity[11], Germany and France have signaled delays in nuclear plant closures to bolster energy security and provide non-gas derived electricity to citizens. These are plants that were scheduled for closure as countries try to shift toward greater reliance on renewable sources of energy, and ultimately those countries will want to return to clean energy sourcing.

While many people think the war will end soon because President Putin and Russia are running out of money, weapons, and support, that is not exactly true. China and India are buying more Russian oil now than before the Ukraine invasion because Russia is forced to sell at huge discounts since Western countries aren’t buying. Sudan has given Russia access to a port on the Red Sea, which makes it easier to transport gold and other raw materials from Africa to Russia. In exchange, Russia has been supplying a host of African governments with mercenaries to help fight insurgents and advisers to help overcome political opponents. So even though the West has sanctions against Russia, for much of the rest of the world it is still business as usual.

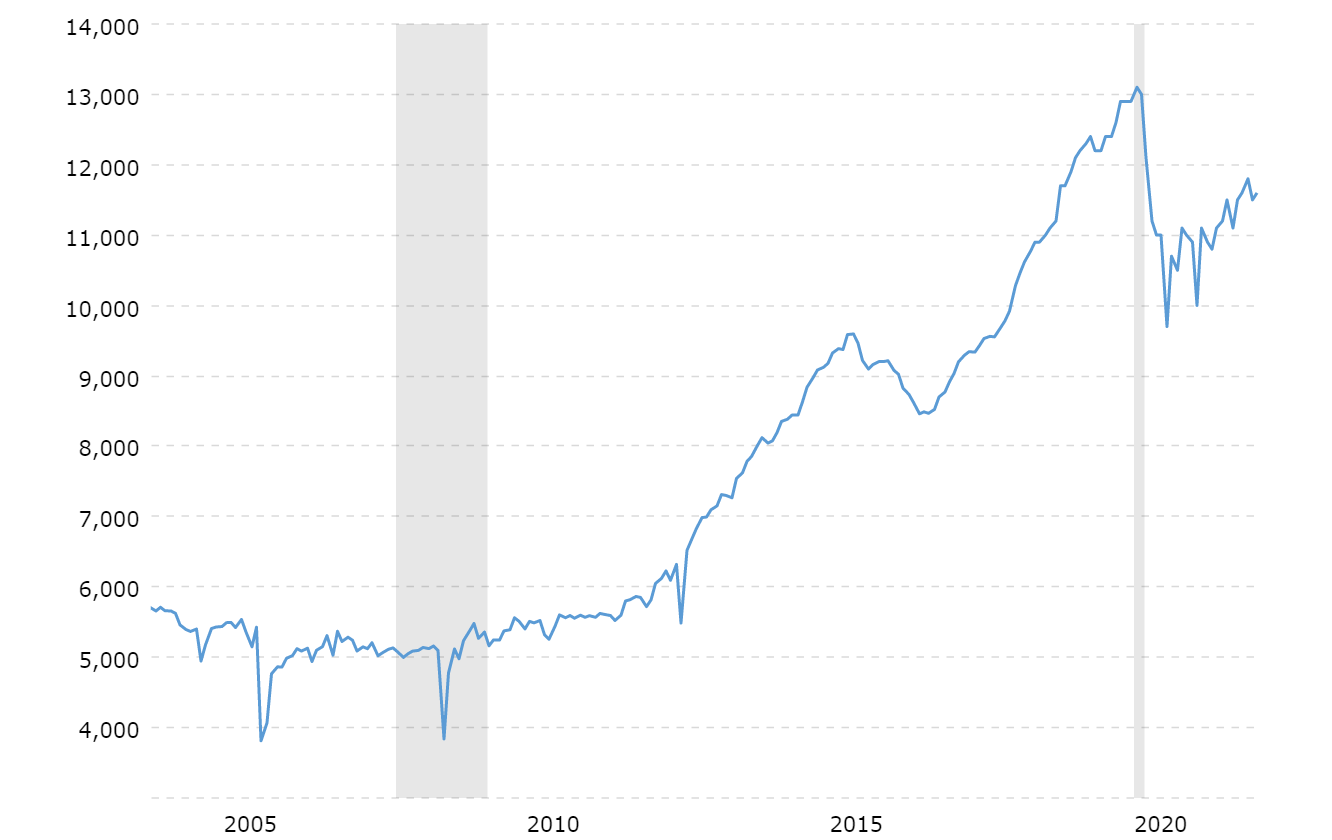

What are the consequences of a prolonged energy price spike? One, there could be a decline in support for Ukraine. Already there are talks in Europe about whether the sanctions are worth the financial pain to citizens, and when countries have trouble keeping their lights on, dissatisfaction with sanctions will be more pronounced. Two, high energy prices could continue to push inflation higher. Most goods in the U.S. move by trucks, and high diesel prices will ultimately be reflected in end prices to consumers, which erodes consumers’ spending power and leaves consumers with less disposable income, and ultimately, this affects corporate earnings, which affects market returns. This may also lead the Federal Reserve to increase rates even higher, causing a recession in the U.S.. Third, there might be long-term environmental consequences as plans to shift away from fossil fuels are delayed.

No easy answers other than that the law of supply and demand tells us that energy prices will remain high and will not come down unless either supply increases or demand decreases. This is one of the issues investors are wrestling with as they try to determine the direction of markets over the coming months and years.

Disclosures

This material is solely for informational purposes and shall not constitute a recommendation or offer to sell or a solicitation to buy securities. The opinions expressed herein represent the current, good faith views of the author at the time of publication and are provided for limited purposes, are not definitive investment advice, and should not be relied on as such. The information presented herein has been developed internally and/or obtained from sources believed to be reliable; however, neither the author nor Manchester Capital Management guarantee the accuracy, adequacy or completeness of such information.

Predictions, opinions, and other information contained in this article are subject to change continually and without notice of any kind and may no longer be true after any date indicated. Any forward-looking predictions or statements speak only as of the date they are made, and the author and Manchester Capital assume no duty to and do not undertake to update forward-looking predictions or statements. Forward-looking predictions or statements are subject to numerous assumptions, risks and uncertainties, which change over time. Actual results could differ materially from those anticipated in forward- looking predictions or statements. As with any investment, there is the risk of loss.

It is once again that most joyous time of year where we step back to take time with our families, reflect on the accomplishments of the year that has...

For ultra high-net-worth (“UHNW”) families, integrating health into wealth planning isn’t optional — it’s essential for legacy,...

Can you invest in a way which is environmentally and socially conscientious while still producing solid returns? ESG—shorthand for Environmental,...