The recent swoon in the market could be attributed to confusion and uncertainty around the United States’ new tariff and trade policy. The Trump administration has announced a flurry of current and potential future tariffs, that are changing and evolving almost daily, making it difficult for investors to adequately understand the goals, the economic impacts, and the potential unintended consequences. As such, the market has traded down on general uncertainty about our overall trade policy.

Tariffs were a campaign promise to rectify certain inequities among our trading partners. As expected, shortly after the inauguration, the new administration announced tariffs on three of our largest trading partners. These tariffs were presented as a way to pressure Canada, Mexico, and China to assist with curtailing our immigration and fentanyl problems. Some tariffs were imposed, some changed, some delayed, and some are still being negotiated. The lack of clarity has caused confusion as to what goods are impacted, when the tariffs take effect, for how long, and to what end. Moreover, it isn’t widely understood whether the tariffs are designed to help with our budget deficit, equalize the trading discrepancies among our trading partners, or leverage our economic strength over other countries. We will try to make sense of our tariff and trade policy herein.

Initially, the new administration threatened a blanket 25% tariff on all goods imported from Mexico and Canada under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), which dates back to the Carter administration. Citing the IEEPA allowed the U.S. to circumvent the U.S., Mexico, and Canada Agreement (USMCA), the free trade agreement that replaced NAFTA in July 2020. An Executive Order citing the IEEPA as justification to impose tariffs has never been done before. This strategy would ensure legal challenges, which is probably why the administration postponed full implementation. The actual tariffs that have been imposed thus far in 2025 are as follows:

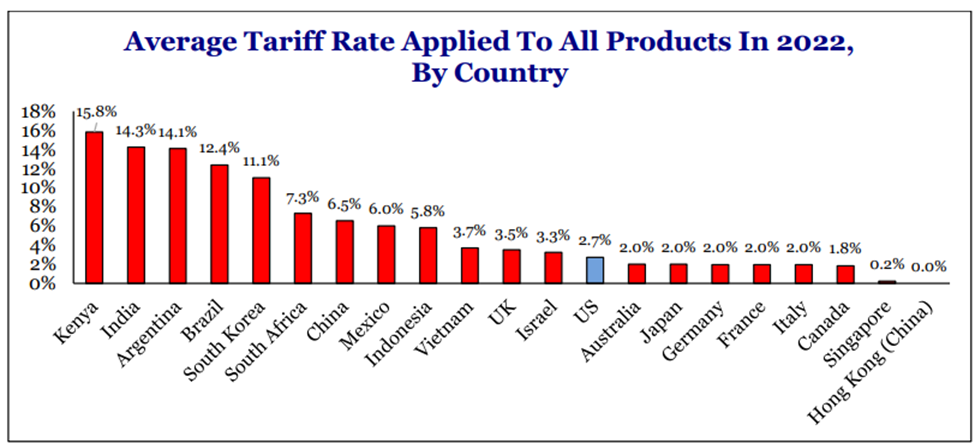

Now, investors are looking to April 2nd when the new administration is planning to announce reciprocal tariffs. Reciprocal tariffs are matching tariffs that will be imposed on a country-by country basis based on each country’s tariffs on U.S. goods. Reciprocity includes accounting for any non-tariff barriers to trade as well.

Reciprocal tariffs are not expected to raise nearly as much in tariff revenue but are easier to justify. Their purpose is to act as a deterrent and to level the playing field. Recent reports from the administration and the commerce department suggest that there will be some “flexibility” as it will be implemented using a “two-step” process, potentially allowing countries to negotiate or adjust their own trade policies before these tariffs are fully enforced. For instance, Reuters reports that India is considering tariff cuts on $23 billion of U.S. imports to protect $66 billion worth of exports.

The new administration is also considering sectoral tariffs—tariffs imposed on specific sectors like pharmaceuticals, autos, and semiconductors. Sectoral tariffs are designed to close trade deficits with specific countries or encourage the re-shoring of particular industries for national security purposes. One example is Ireland, where approximately 25% of our pharmaceuticals are manufactured. Companies such as Pfizer, Merck, Abbvie, and Johnson & Johnson moved their companies and/or production facilities to Ireland through “reverse tax inversions”, a popular technique in the 2010’s that substantially reduced the taxes these companies paid on the earnings for popular drugs. The imposition of new tariffs on imported pharmaceuticals could potentially lead to even higher costs for healthcare.

According to Strategas Research, the tariffs introduced to date as well as the potential reciprocal and sectoral tariffs could generate approximately $235 billion, or 0.75% of U.S. GDP. However, these tariffs might also come with consequences—many of our most important trading partners have announced potential retaliatory measures if these tariffs are put in place. The chance of an escalating trade war cannot be ignored and is a contributing factor to the market’s current unease.

From what we can tell, the administration’s tariff strategy seeks to raise revenue and encourage domestic production. This strategy was attempted by President Hoover with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930. The purpose was to protect U.S. farmers by imposing tariffs on imports of agricultural products. Congress approved the Act despite 1,028 economists signing a letter opposing it. The tariffs resulted in boycotts and retaliation by our trading partners, most notably Canada. U.S. farmers had been producing at a surplus and relying on exports, but after Smoot-Hawley and the resulting retaliatory tariffs, they were unable to export their produce. By 1934, global trade had dropped 66% and employment cratered at farms and export-dependent industries, which further exacerbated the U.S.’s already dire economic situation.

Regardless of the rhetoric, tariffs are a tax, and someone must bear the tax burden. Generally, producers of goods with low demand elasticity (i.e. goods with limited substitutes), can pass most of the tax impact on to their customers through higher prices. In these situations, the customer bears the burden of the tariff, which is inflationary. Conversely, producers of goods with high demand elasticity (i.e., goods with many substitutes like commodities), have difficulty passing the tax on to their customers, so the producers absorb most of the cost increase. This hurts the producer’s margins and ultimately their profits. Lower corporate profits mean less government revenue from corporate taxes. Our three largest imports from Canada are crude oil, gas, and cars, while Canada’s largest imports from the U.S. are cars and automotive parts, machinery, and electronic equipment. Although the U.S. has an advantage, there will be inflation pressures. We are trying to determine if the inflation pressures from tariffs could be largely offset by reduced government spending.

Businesses and consumers appear to be taking a wait-and-see approach. According to the most recent data, consumer confidence is declining, retail sales have been weaker than expected, and some CEOs have warned of softening consumer trends. The Atlanta Fed’s real-time GDP tracker shows notable slowing this quarter. It is possible that the U.S. may see GDP decline in the first quarter while trade negotiations are ongoing. Though, we don’t see evidence of a recession at this time. The main issue is uncertainty and the lack of clarity surrounding the plans and goals for Trump’s tariff strategy. This policy uncertainty translates directly into market volatility. We are looking forward to more guidance and clarity on April 2nd. We stand ready to evaluate the administration’s actions and make appropriate adjustments in client portfolios, if needed.

Sources: Strategas, WSJ, Reuters

Disclosures

This material is solely for informational purposes and shall not constitute a recommendation or offer to sell or a solicitation to buy securities. The opinions expressed herein represent the current, good faith views of the author at the time of publication and are provided for limited purposes, are not definitive investment advice, and should not be relied on as such. The information presented herein has been developed internally and/or obtained from sources believed to be reliable; however, neither the author nor Manchester Capital Management guarantee the accuracy, adequacy or completeness of such information. Predictions, opinions, and other information contained in this article are subject to change continually and without notice of any kind and may no longer be true after any date indicated. Any forward-looking predictions or statements speak only as of the date they are made, and the author and Manchester Capital assume no duty to and do not undertake to update forward-looking predictions or statements. Forward-looking predictions or statements are subject to numerous assumptions, risks and uncertainties, which change over time. Actual results could differ materially from those anticipated in forward-looking predictions or statements. As with any investment, there is the risk of loss.

Today’s most dangerous cyber threats don’t come from hackers breaking into systems- they come from someone convincing you to open the door for...

As investment stewards, we at Manchester Capital seek to preserve, protect, and grow client assets given the prevailing market, economic, and...

The recent swoon in the market could be attributed to confusion and uncertainty around the United States' new tariff and trade policy. The Trump...