Until 2021, the U.S. economy benefited from a long period of modest inflation. The Consumer Price Index averaged just 1.88% for the prior 10 years, aided mostly by technology, e-commerce, and supply-chain efficiency gains. Then the pandemic hit, causing tremendous supply-side disruptions and widespread economic uncertainty. As we navigated Covid-19, the government provided a steady stream of stimulus through unprecedented monetary and fiscal outlays. It worked, at least temporarily, as the economy recovered rather quickly as did employment and the capital markets.

Demand continued despite supply constraints and bottlenecks resulting from Covid-19 safeguards which led to steadily increasing inflation.

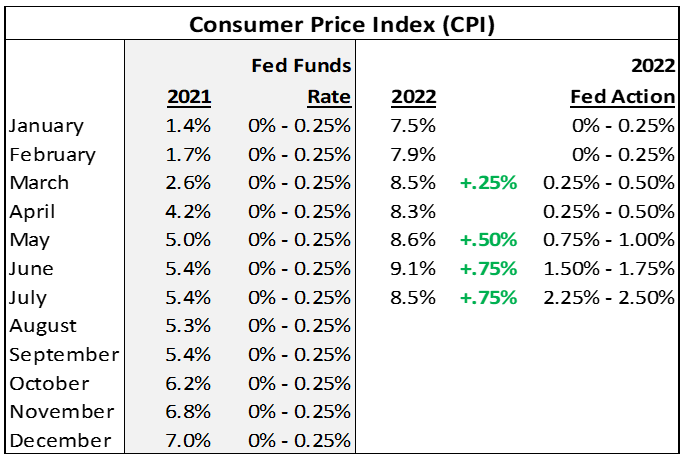

This year, inflation is averaging an annualized 8.3%, the highest in more than 40 years. Pandemic-related inflation pressures did not gradually subside as the Fed initially thought, with Fed Chair Powell saying inflation was “transitory”. This delayed a policy response by the Fed, putting them behind the curve and potentially exacerbating the problem. Instead, inflation has persisted as the stimulus was slow to be removed and consumer demand remains robust. Now, despite Fed action, we are seeing the “stickier” components of inflation, such as wages and rents, starting to rise.

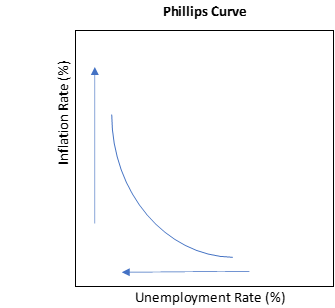

Although the July inflation report showed a slight moderation in the annualized rate of inflation (declining from 9.1% to 8.5%), the labor market continues to be tight, maintaining pressure on wages. This resilience in the unemployment rate could be an ominous sign of continued high inflation as reflected in an economic relationship known as the Phillips Curve. The Phillips Curve shows the relationship between the inflation rate and the unemployment rate.

According to the Phillips Curve, as unemployment falls there is a tendency for consumer prices to rise. Intuitively, this makes sense—more workers earning wages means more individuals with money to spend, creating more competition for consumer goods, which causes prices to rise.

From the Federal Reserve’s perspective, strength in the labor market provides cover for the Fed to be more aggressive fighting inflation. During Fed Chairman Powell’s most recent public address at the Jackson Hole Symposium of Central Bankers, Powell said the Fed could raise policy rates to be restrictive enough, and hold them high for long enough, to bring inflation back down, even if it causes economic pain. This was a decidedly hawkish tone from Chairman Powell, and a change of pace for the Fed. The stock market dropped 3.3% after Powell’s comments.

Interestingly, Powell noted in his speech, “the historical record cautions strongly against prematurely loosening policy.” The “unconditional” pursuit of price stability may indeed cause economic “pain,” but that pain was understood and considered a price worth paying. We believe Powell is referring to the failed effort by the Federal Reserve to curtail inflation in the 1970s. That was the last time the U.S. experienced persistently high inflation. At the time, the Fed pursued a “stop-and-go” strategy to balance surging inflation and a sputtering economy. During “stop” periods, when inflation escalated, the Fed would raise interest rates to reduce inflationary pressures. During “go” periods, the Fed would lower interest rates to loosen the money supply and attempt to reduce unemployment. This approach ultimately failed as there was too much short-term reliance on the relationship between inflation and unemployment (i.e., the aforementioned Phillips Curve), leading to stagflation and high unemployment by the late 1970s.

While unemployment trended down slightly by the end of the decade, inflation continued to rise reaching 11% at the end of 1979. Then, Paul Volcker was appointed Chairman of the Fed, largely due to his aggressive view on fighting inflation. Volker argued that for the sake of long-term economic stability, the Fed’s primary concern should be curbing inflation. He immediately shifted Fed policy to reduce the money supply rather than just focus on nominal interest rates. Volker was also adamant about changing expectations. He needed market participants to believe the Fed was not bluffing and was going to tighten until inflation notably subsided, even if the economy suffered. “We have set our course to restrain growth in money and credit. We mean to stick with it” (Volcker 1981). He used a “start-and-stop” approach to tightening. Volker would raise interest rates, pause, then raise them again. In the process, Volker took nominal interest rates to nearly 20% and he remained steadfast even as the 10-year Treasury advanced to 15% and the unemployment rate eclipsed 10%.

Volker’s approach was not without criticism. The high nominal rates were particularly harmful to the farming and construction sectors. At one point, farmers protested the Fed by driving their tractors onto C street in Washington, D.C. to block the Federal Reserve Building.

Although economically painful, Volker’s interest-rate discipline ultimately proved successful in suppressing inflation and laying the groundwork for steady economic growth for years to come. Inflation peaked at 14.8% in March 1980 then subsequently declined to below 3% by 1983.

We believe Powell is moving towards Volker’s method and is taking the “pivot” off the table, meaning the Fed will not immediately begin reducing rates once inflation begins receding. Powell appears to want the market to recognize that he is pursuing Volcker’s strategy and will raise rates as necessary, and hold them for as long as necessary, until he is confident inflation has been suppressed. Powell recognizes his actions will cause short-term economic pain through higher unemployment, higher cost of capital, lower economic activity, and stock and bond market weakness. Powell considers, as Volcker did, that persistent elevated inflation is more damaging to longer-term economic stability and its costs fall heavily on those least able to bear higher prices. Taking Powell at his word, we expect short-term rates to be higher for longer than previously expected, and as such, we continue to approach this market conservatively and cautiously.

August’s inflation will be reported September 12th. Economists generally expect inflation to come in at 8.3% indicating that inflation has a long way to go to reach the Fed’s target of 2.0%. Even though the last two 0.75% Fed rate increases were the most rapid increases in 32 years and put the Federal Funds interest rate in a range of 2.25% – 2.50%, Fed watchers predict another 0.50% to 0.75% increase at the next Fed meeting on September 21st. If Powell is following Volker’s playbook, that increase won’t be the last, meaning we will likely see increases into 2023.

Disclosures

This material is solely for informational purposes and shall not constitute a recommendation or offer to sell or a solicitation to buy securities. The opinions expressed herein represent the current, good faith views of the author at the time of publication and are provided for limited purposes, are not definitive investment advice, and should not be relied on as such. The information presented herein has been developed internally and/or obtained from sources believed to be reliable; however, neither the author nor Manchester Capital Management guarantee the accuracy, adequacy or completeness of such information.

Predictions, opinions, and other information contained in this article are subject to change continually and without notice of any kind and may no longer be true after any date indicated. Any forward-looking predictions or statements speak only as of the date they are made, and the author and Manchester Capital assume no duty to and do not undertake to update forward-looking predictions or statements. Forward-looking predictions or statements are subject to numerous assumptions, risks and uncertainties, which change over time. Actual results could differ materially from those anticipated in forward- looking predictions or statements. As with any investment, there is the risk of loss.

It is once again that most joyous time of year where we step back to take time with our families, reflect on the accomplishments of the year that has...

For ultra high-net-worth (“UHNW”) families, integrating health into wealth planning isn’t optional — it’s essential for legacy,...

Can you invest in a way which is environmentally and socially conscientious while still producing solid returns? ESG—shorthand for Environmental,...