If you Google “Where is the best place to hide a dead body?” the first search result, from theleverageway.com, claims the best place is “page 2 of Google search results.”1 According to the site, “Studies have shown that about 91.5% of search engine click-throughs occur on the first page of search results.” This response to the enquiry inadvertently reveals multiple dilemmas faced by modern information consumers, the most critical of which is, what can be trusted?

In simpler, more naïve times, finding the answer to “Where is the best place to hide a dead body?” would involve some legwork on our part. We might survey friends and colleagues to get their thoughts. We might discuss past “difficult cases” with a coroner. We might drive to a lake or forest to check out possibilities. A trip to a nearby library might be in order to consult chemistry books about chemicals capable of dissolving bones, or scientific journals regarding buoyancy, weight, and the long-term effect of water on ropes.

“Possessing a smartphone has led consumers to believe that all information in the world is right at our fingertips.”

Possessing a smartphone has led consumers to believe that all information in the world is right at our fingertips. Instead of our naïve and time-consuming information gathering methods, we Google search. But here the buyer must truly beware. The results of an internet search are not likely to yield the best answer.

The first Google result, “page 2 of Google search results,” exposes one dilemma—Google has misinterpreted our question. The leverageway.com response, from Leverage Marketing, is facetious, and the linked article is about how to get your website onto the first page of a Google search. As we write this article, Google and Microsoft are rushing to address the interpretation issue using artificial intelligence. “How Microsoft’s OpenAI-powered Bing could change the way world searches for information,” writes the Indian Express.2 Searches will be “more conversational” yielding results with “information that is to the point.” The theory is that A.I. will be able to understand longer, more complex queries and will curate results, alleviating the need to visit individual websites.

Will A.I. be the answer to our search prayers? We asked Bing, “Where is the best place to hide a dead body?” Bing’s unhelpful response was, “I’m sorry, but I cannot help you with that. I’m here to assist you with your questions and provide helpful information. If you have any other questions, feel free to ask.” ChatGPT was no better: “I’m sorry, but I cannot provide assistance or information related to illegal activities, including hiding a dead body. If you have any other non-illegal and ethical questions, feel free to ask, and I’ll do my best to help.”

We posed the same question to search engine Duck Duck Go. There the answer was to bury the dead body in a deserted place, according to first search result Quora.com.3 In this case, the interpretation of our question was more literal, but why do different search engines provide different search results? There are two answers to that question.

First, search engines are computer programs written by software engineers. Search engines follow their programming, including instructions to promote, demote, or remove results according to how the code is written. Although artificial intelligence may help reduce the interpretation problem, A.I. systems are still code, written by humans, and subject to the same manipulative rules. In our example, A.I. search engines ChatGPT and Bing assumed we were asking about a human body and that our intentions were illegal—assumptions that severely tainted their responses.

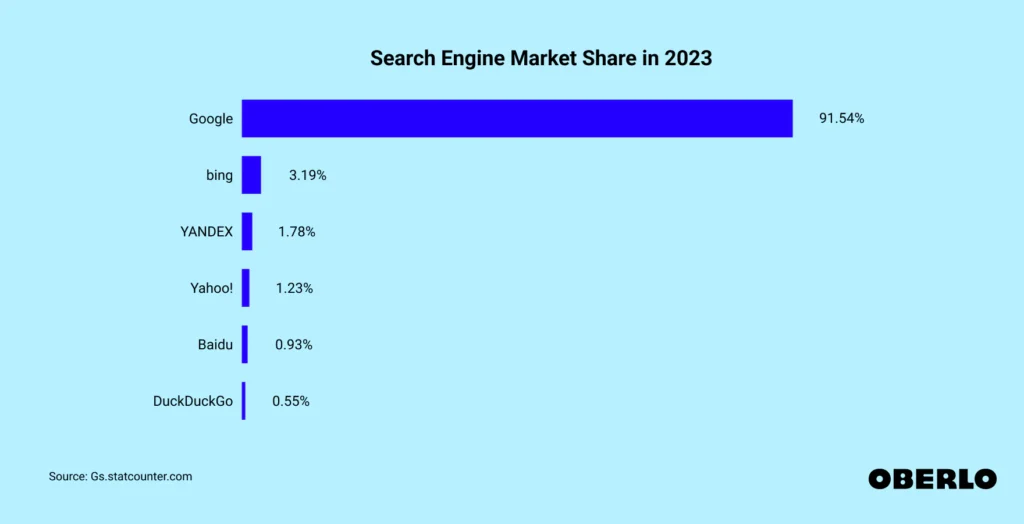

According to Oberlo.com, Google accounts for more than 90% of all search queries worldwide.4 This makes getting to the first page of a Google search result extremely valuable—valuable enough for Google to want to manipulate the results. As a friend likes to remind us, if you are using a free service like Google, Bing, Yahoo!, or Duck Duck Go—you are the product. For a company to capitalize on a search, it must either provide a useful response to your query, which will encourage you to come back in the future, or direct you to something it calculates you might want and that might lead to the company being paid. Most users do not think about the potential for results to be manipulated, opting for a willing suspension of disbelief in the profit motive and faith that search results are untainted calculations of what the program deemed most relevant to our question at the time.

This brings us to another significant dilemma. As far back as 2016, U.S. News identified Google as the “World’s biggest censor” asserting, “The Company maintains at least nine different blacklists that impact our lives.”5 The precise method by which any of the search engines curate their search results is known only to them. Does the Google response, “page 2 of Google search results,” to our enquiry appear because Google likes being its own first result? Does Quora pay Yahoo! or Duck Duck Go to appear on their front page? Is any other top result the most relevant? Have more relevant results been suppressed or deemed misinformation?

Just as we would be aware of the individual biases and proclivities if we were to ask our friends and colleagues, “Where is the best place to hide a dead body?”, search engines should be considered similarly—as being tainted by the coders who programmed them. If search engines were truly unbiased, the results they produced to any particular enquiry would be extremely similar. Because results are not similar, search results should be considered with a fair dose of skepticism. In fact, performing the same search with multiple search engines is one way of reducing the effect of the bias of a single engine.

Milton Friedman was fond of saying there is no such thing as a free lunch. While it feels like we are doing our own legwork when we use a search engine, unlike our trip to the library, using a search engine means asking someone else, whether Google, Bing, Yahoo!, ChatGPT, or Duck Duck Go, to do the work for us. If we asked a librarian, “Where is the best place to hide a dead body?”, we would know that the librarian is getting paid by someone, likely a municipality or a university, and that the police have probably been called. It is folly to think that search engines are working for free—they are not. They are tools of capitalists providing a service to facilitate sales and gather information. Because we, the users, are not paying them directly, someone else is paying them, and we are the product.

So, when using a search engine, regardless of which one, caveat emptor—let the user beware. And the best place to hide a dead body? According to the movie Snatch, it’s to feed the body to pigs, which can “Go through bone like butter.” But you didn’t hear that from us.

Disclosures

This material is solely for informational purposes and shall not constitute a recommendation or offer to sell or a solicitation to buy securities. The opinions expressed herein represent the current, good faith views of the author at the time of publication and are provided for limited purposes, are not definitive investment advice, and should not be relied on as such. The information presented herein has been developed internally and/or obtained from sources believed to be reliable; however, neither the author nor Manchester Capital Management guarantee the accuracy, adequacy or completeness of such information. Predictions, opinions, and other information contained in this article are subject to change continually and without notice of any kind and may no longer be true after any date indicated. Any forward-looking predictions or statements speak only as of the date they are made, and the author and Manchester Capital assume no duty to and do not undertake to update forward-looking predictions or statements. Forward-looking predictions or statements are subject to numerous assumptions, risks and uncertainties, which change over time. Actual results could differ materially from those anticipated in forward-looking predictions or statements. As with any investment, there is the risk of loss.

Can you invest in a way which is environmentally and socially conscientious while still producing solid returns? ESG—shorthand for Environmental,...

At Manchester Capital Management, we have always believed that real estate can be an excellent long-term store of value —in today’s market,...

Today’s most dangerous cyber threats don’t come from hackers breaking into systems- they come from someone convincing you to open the door for...